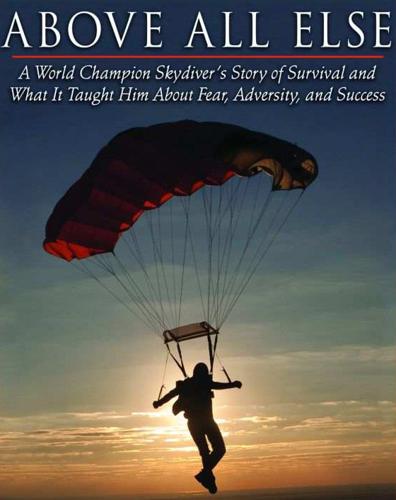

Above All Else (Excerpt) - Dan Brodsky-Chenfeld

In this book world famous competitive skydiver and coach Dan Brodsky-Chenfeld presents proven tools and techniques for success and explains how they can be used in everyday life. Dan survived a plane crash from which sixteen of the twenty-two people on board were killed. He was left critically injured and woke up from a six-week-long coma with a broken neck, broken skull, severe head trauma, a collapsed lung, and other serious internal injuries. Against all odds, Dan recovered and went on to become one of the greatest competitive skydiver in the world.

His book is available on Amazon.com

Waking Up

Something was wrong. I was groggy, fading in and out. My body felt tired, weighted down. What was going on?

I tried to see but my eyelids were too heavy to lift. I summoned all the strength I could but still didn’t have the power to peel them open. The last thing I could recall was training with my new skydiving team, Airmoves. After nine years of competition, much of which was spent living in my van and eating out of a cooler so that I could afford team training, the owners of the Perris Valley Skydiving Center in California had presented me with a team sponsorship opportunity. I would get to pick and run the team. They would cover the training costs.

This was it, the opportunity I had always hoped for. Since money wasn’t an issue, I was able to pick the teammates I most wanted. The first person I called was James Layne. I had known James since he was eleven and had taught him to jump when he was only fourteen. His whole family had worked at my drop zone in Ohio.

James was like a little brother to me. Even before his very first jump seven years earlier, we had decided that someday we were going to win

the national and world championships together. This was our chance, a dream come true.

Troy Widgery was next on my list. Troy was a young entrepreneur and good friend whom I had coached when he was on the University of

Colorado Skydiving Team. At the collegiate national championships a year earlier, I had told James and Troy that somehow, someday, I was going to get them both on my team.

Richard Stuart had been the camera flyer on my previous team, the Fource. But like me, Richard still just hadn’t had enough of team training and competition.

To fill the one remaining position, I held tryouts. Tom Falzone outperformed

the rest and completed the team lineup. Perris Airmoves was born.

We were five months into our training and had made about 350 practice jumps. Everything was going better than I had ever imagined, and I have quite an imagination. We were improving at an unheard-of pace and had already gone head-to-head with some of the top teams in the country. The U.S. Nationals gold medal was in our sights.

And then . . .

The crust on my eyelashes glued them shut. Using the muscles in my forehead, I finally pried them open a crack. A faint white light was all I could see, like I was inside of a cloud. It was silent. Where was I waking up? Was I waking up? Was I dead?

I had no idea what was happening, how I got here, or what was going on. But I did have one absolutely vivid image in my head, a crystal clear picture of something that seemed to have happened just moments before waking up. It wasn’t a dream. It was as real as any real-world experience I had ever had. I could remember the entire thing, every action, every word, and every thought.

It went like this: I was in free fall. Almost as if I had just appeared there. I love free fall, and finding myself there at that moment seemed

natural. I was at home, at peace, part of the infinite sky.

But after a few seconds I noticed that this wasn’t normal free fall. It was quieter. The wind wasn’t blowing as fast. I wasn’t descending.

A gentle breeze was suspending me. It was okay, it was fine. I was floating, flying, but it wasn’t right. What was I doing there? I wasn’t

afraid. I felt safe, but confused.

I looked up and saw James flying down to me just as if we were on a skydive together and he was “swooping” me. His expression was that silly, playful smile he so often had in free fall. He was obviously not confused at all. He knew exactly where he was and what he was doing there.

He flew down and stopped in front of me. Still with a smile on his face, he asked, “Danny, what are you doing here?”

I answered, “I don’t know.”

James said, “You’re not supposed to be here, you have to get back down there.” I began to get a grasp of the situation.

I asked him, “Are you coming with me?”

His expression changed to one with a hint of sadness. He said, “No, I can’t.”

I tried to persuade him to change his mind, “C’mon, James, we were just getting started. You gotta come with me.”

James raised his voice, interrupting me. “I can’t!” It was obvious that the decision was final. It seemed as if it wasn’t his decision. He

continued with a gentle smile. “I can’t, but it’s okay. There are more places to go, more things to do, more fun to have. Tell my mom it’s okay. Tell her I’m okay.”

For a few seconds we just looked at each other as I accepted this for the reality it was. He changed his tone and spoke with some authority

as he gave me an order. “Now,” he said, “you need to get back down there. You need to go get control of the situation.” I unquestioningly

accepted this as well, still not knowing what the situation was that he was referring to.

James stuck out his hand palm down, the way we always did when practicing our “team count,” our “ready, set, go” cadence we would use to synchronize our exit timing. A couple of minutes before exiting the plane on a training jump, we would always huddle up and practice this count. The purpose was as much to get psyched up for

the jump as to rehearse the cadence. I put my hand on top of his. He put his other hand on top of mine. I put my other hand on top of

his. We looked each other in the eyes. Both of us with gentle smiles of love and confidence and sadness. James started the count. “Ready.” I

joined in as we finished it together. “Set. Go.” As was our routine, we clapped and then popped our hands together, locking them in a long,

strong, brotherly grasp.

James had one more thing to say, and he said it with absolute certainty,

“I’ll see you later.” It was clearly not a “good-bye.” I had no doubt that we would see each other again. Before I had even thought

about an answer, the words “I know” came out of my mouth. Slowly I started to descend. As I did, James began to fade from my grip. The wind picked up as I was now falling through it, no longer suspended by it. Everything went black.

As I woke, James’s words, “Get control of the situation,” still rang clearly in my mind. If only I knew what the situation was. I knew I wasn’t dead. I squinted, trying to see more clearly. The white light slowly brightened. A few small red and green lights came into view. As if coming from a distance, faint electrical beeping sounds began to reverberate from the silence.

My vision started to sharpen. I could see I was surrounded with lights, gauges, hoses, and wires running in every direction. The glowing white light wasn’t the heavens. It was the bedsheets and ceiling paint of an ICU hospital room.

I stared straight up from flat on my back, the position I found myself in. What’s the situation? I thought that James and I must have been in some kind of accident together. James was gone and I wasn’t. I tried to pick my head up to look around the room. My head wouldn’t move. I tried to turn my head to look to the side; it wouldn’t move. Oh my God, I thought. I can’t move my head. I’m paralyzed. It can’t be true. Don’t let it be true. This can’t be the situation. I was filled with a sense of fear far greater than anything I had ever experienced before. I felt myself starting to give up and caught myself. Don’t panic, don’t panic. I closed my eyes, took a breath, and tried to calm down. It’s got to be something else, there has to be more. I told myself not to come to any conclusions too soon, to pause and re-evaluate the situation. I started again.

I opened my eyes. I could see a little more clearly now, and there was no doubt I was definitely in a hospital bed complete with all the bells, whistles, buzzers, and instruments. I tried to move my head again. It wouldn’t budge. “Stay cool, stay cool. Try something else,” I

told myself.

I tried to move my toes. I thought I felt something, but I couldn’t lift my head to see them to confirm. I remembered hearing about

people who were paralyzed but had ghost movements when it felt as though they could move even though they couldn’t. “Stay cool, Dan, stay cool. Look for options. Try something else.” I had to talk myself through it every step of the way.I tried to wiggle my fingers. It felt like they moved. I tried to move my hands. I could swear they worked. Did they move? I couldn’t turn my head to see my hands but nearly stretched my eyes out of their sockets trying to look down to verify that my hands were actually moving.

Peering past the horizon of the bedsheet, there were no hands in sight. I tried to lift my hands higher. They felt so heavy. Were they moving, or was it my imagination wishing them to move? Slowly, I saw the bedsheet rise. Like the sun rising in the morning, slow but certain. I brought my hands all the way up right in front of my face, trying to prove to myself that it wasn’t a hallucination. I stretched out my fingers, clenched my fists, and then stretched them out again. I put my hands together to see if my right hand could feel my left and my left hand feel my right. They worked. Yes! What an incredible relief. My arms and hands weren’t paralyzed. Okay, so far so good, back to my legs. I tried again to move my toes and lift my feet. They were too far away to see and too heavy to lift. I gathered all the strength I had, as

if I was trying to bench-press four hundred pounds, and focused it on my knees. Ever so slowly, the bedsheet started to lift. Slowly my knees came up high enough that I could see they were moving. I wasn’t paralyzed, not at all.

Get Dan's Book from Amazon.comI still didn’t know what the situation was, but no matter what, it wasn’t as bad as I had feared. I felt a sudden relief, and though I had never been a person who prayed very often, without even thinking I found myself thanking God forlessening my burden.

Why couldn’t I move my head, though? I reached up with both my newly working hands to feel my head. As I did, I came in contact with two metal rods. As I explored further I realized my head was in a cage. I couldn’t move my head not because I wasn’t capable but because it was being held still by a halo brace.

My neck must be broken. But for a person who moments earlier thought he was completely paralyzed, a broken neck seemed like the

common cold. The experience of thinking I was paralyzed from head to toe was truly a gift. It would forever put things in perspective for

me. I decided at that moment that I would never complain about my injuries, no matter what they were.

But what had happened? I asked the doctor, but he skirted the question and instead filled me in on my condition. In addition to breaking my neck, I had a collapsed lung, cracked skull, a severe concussion, and crushed insides causing other internal injuries. It’s hard to believe, but none of this really fazed me. It was still much better

news than I had feared. I asked him again, “What happened?” He acted like he didn’t hear me.

The doctor was concerned about the nerve and brain damage but seemed confident that I would ultimately be able to walk out of the hospital and lead a relatively normal life, as long as my normal life didn’t include any contact sports or rigorous activity at all. I would

certainly never skydive again.

A little while later, Kristi, my girlfriend, came in. I asked her what had happened, but she dodged the question. I kept asking her, pushing

her; I had to know. Finally she said, “It’s bad, Dan, it’s so bad.” That was the first time it occurred to me that if James and I were in an accident of some kind, it was likely that the other members of Airmoves were in the same accident. I asked her again what had happened.

“It’s so bad” was all she could say. I pushed her relentlessly. Finally, she told me. There was a plane crash. A plane crash? I hadn’t

even considered a plane crash. I realized what that could mean and tried to prepare for the worst, that my entire team may be gone. The

sudden emotional barrage that hit me was overwhelming. I was starting to lose control and caught myself. I closed my eyes, took a breath,

and calmed myself down.

I later learned that Kristi had been by my side since the crash. She and my friends and family did not know how, if and when I woke up,

they would tell me that James was gone. I asked her, “How’s my team?” She tried to speak, but still, the only words she could muster were, “It’s bad, Dan, it’s so bad.”

I needed an answer. I said, “I know James is gone. How is the rest of the team?” She froze in disbelief. She looked at me, staring deeply

into my eyes, and asked, “How do you know that?”

I answered directly, “He told me.”

She continued to stare at me, wondering how that was possible. Almost relieved that I already knew about James, Kristi told me that, compared to me, my other teammates were fine. Troy and Tom were banged up and had broken a few bones. Troy had to have surgery on his hip. But all things considered, they were basically okay.

Richard had missed the plane. His camera helmet broke just minutes before we boarded, and he had asked another cameraman to take his place while he went to fix it. In the thousands of training jumps Richard and I had together, I could never remember him missing a jump. Kristi was quiet. There was more.

We were flying in the Twin Otter, which carries twenty-two people. It was worse than I thought, way worse. For some reason, I had assumed that Airmoves had been alone in a single-engine Cessna. Of the twenty-two people on board, sixteen had died in the crash. Most of them my friends, including Dave Clarke, the cameraman who took Richard’s place.

The emotional bombardment continued as Kristi told me who we lost. The names included members of Tomscat, a team from Holland that I was coaching, the pilots, instructors, and camera flyers who worked at the skydiving school, and students who were there for their first jump, in what was supposed to have been an experience of a lifetime for them. Kristi was right: It was bad. So, so bad.

Because I was just learning about this, I had assumed that it had all just happened. As I was absorbing this information, I was hit with

another shocker. The crash had occurred over a month ago. I had been in a coma for nearly six weeks. How could that be? I picked up my

arms and held them in front of my face. They looked skeletal. I had lost forty pounds. I touched my face and discovered a beard. It was true. What hell the families and friends must have been going through over the last month while I had the luxury of being unconscious. What sorrow and grief they must have been experiencing. I felt so badly for them, and guilty that I wasn’t there to be with them through this difficult time.

It immediately occurred to me that I had to be strong. It may have been new to me, but they had been dealing with it for over a month. I

was experiencing this grief for the first time, but I would have to do so on my own. I didn’t want to drag my friends and family back through

it all again.

If only they knew what I knew. If only James had been able to share with each of them what he shared with me. I knew that our friends

were gone, but that they were okay. I knew they had more places to go, more things to do, and more fun to have. I knew we hadn’t said good-bye, only, “See you later.” I wanted to share this with everyone, but I also knew that they would think I was nuts and that the brain damage I had suffered was more severe than they thought. I kept it to myself, except for telling one person. As James had requested, I called his mother, my dear friend Rita, from my hospital bed and passed his message on to her.

“You need to go get control of the situation.” What exactly did James mean? I thought about that a lot. I believe he was alerting me to the fact that I was about to wake up in a different world than the one before the crash. I would be arriving in the middle of a situation that was overrun by sadness, fear, helplessness, and defeat. I believe he was warning me that many people were going to try to define the situation for me and tell me what my limitations were. He was telling me not to be a victim, not to let anyone but me decide my fate and that I didn’t have to let go of my dreams. There was more to “life” than what we experience in this physical world. He was telling me it was all okay. James was reminding me that prior to the crash, I had taken control of my life. I had found an activity that I loved, pushed myself to be the best I could possibly be at it, and set my sights on becoming the best in the world. I had shown the courage to follow my dreams and the faith in the world to believe that the few things that were out of my control would work out as they should. This attitude toward life had never steered me wrong in the past. And it wouldn’t then. I believed him. I trusted him. And I decided.

FOLLOWING YOUR DREAMS

Human beings are born dreamers. Through dreams we explore our limitless imaginations and consider the true possibilities of things we perceive to be impossible. Most great human achievements began as someone’s impossible dream, a crazy fantasy. It was the dreamers of their day who imagined electricity, flying machines, walking

on the moon, running a four-minute mile, or instantly communicating on a cell phone or the Internet. All of these were considered impossible right up until the moment they actually happened. Soon after, they were thought of as everyday occurrences.

Our dreams provide us a stage from which we can fantasize about things that don’t seem feasible within the constraints of our physical

realities. They encourage us to question our often false perceptions of the limits of those realities. Through our dreams we are open to

exploring all possibilities. Without our dreams, we too often surrender to our established limitations and underestimate our true potential.

Dreaming is an essential part of what it means to be human. The same way we are born hungry and need to eat to grow, our minds and

souls crave inspiration and need our imaginations to show us all what we are truly capable of being and doing.

It is human nature to want to expand our capabilities. As long as we can imagine reaching the next level in our chosen field, most of us will instinctively want, and choose, to do so. Once babies have crawled, they want to walk. As soon as they walk, they want to run. Once they

can run, they want to jump. We are rarely satisfied with where we are while we can still imagine, and believe, that we can do more.

Few things have the power to motivate and inspire us to reach for our full potential the way our dreams do. Successful people from every

walk of life—be they athletes, musicians, soldiers, doctors, policemen, firefighters, entrepreneurs, or entertainers (just to name a few)—usually agree on one thing. As children, long before they ever achieved success in their field, they dreamt and fantasized about becoming

great at what they did. It wasn’t money or fame that inspired them as children. It was the pure love and purpose for the activity itself. Most of

them can hardly remember a time when they weren’t insanely passionate about it. Every dreamer is not successful. But every successful person is a dreamer.

As children, we all had dreams like these. But in our early years, most of us were discouraged from believing that we could actually live

our dreams and achieve our highest ambitions. We were more often pushed by family, friends, and society in general to take a more secure

route, keep our expectations low, and avoid failure and disappointment. We were guided by advisors to go after goals they thought we

had the best chance of accomplishing, ones that didn’t demand too much effort from us.

As opposed to looking at things from aperspective of abundance, we chose to see things from a minimalist perspective. Minimal desire leads to minimal goals, requiring minimal effort. Since we would be aiming so low, the likelihood for success was high so there was minimal chance for disappointment. But is the definition of success aiming to be half of what we are capable of being in a field that we tolerate but certainly aren’t passionate about? I don’t think so. And fortunately for me, my family didn’t think so either.

Like it? Read the rest: http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/1616084464/dropzonecom

http://www.danbrodsky-chenfeld.com/